This article was originally posted on Outside Magazine on January 19, 2021.

High school didn’t serve up much adventure, so Devin Murphy signed up to do grunt work on expedition ships that sailed to Alaska, Iceland, Antarctica, and other far-flung places. Turned out to be a pretty great idea.

The ship’s naturalist, in 47B, has filled his cabin with seabirds again. Too many to count. He spent the hours before sunrise stalking the decks, looking for fatigued jaegers and shearwaters that see our lights as an island of rest. This happened in Greenland. No. The South Pacific. No. Off the coast of a black-sand beach in Siberia. One of those. Wherever it is, the room is full of pelagic noise. Gannets. Puffins. One time a great frigate bird perched on a curtain rod and ballooned its ruby red throat up to the size of an elephant’s goiter. It’s hard to keep all these experiences straight. There was so much. That was the point.

People paid a fortune to travel aboard small expedition-style cruises ships that promised experiences of a lifetime, every day. Part of that was being invited into small cabins with world-renowned wildlife experts. The birds stayed in the cabin for a day or two, long enough for the passengers to see them up close. The passengers stayed on board for up to a month, depending on the itinerary. When they disembarked, the ship moved on to the next locale, and new travelers arrived, or new specialty charter companies took over, serving everyone from birders to nudists. They listened to lectures by eminent professors, immersed themselves in exotic cultures, and traversed what Melville called “the watery part of the world.”

One day while I was helping passengers disembark at the end of a Central American cruise, a woman grabbed my forearm.

“Do you keep going with the ship?”

“Yes.”

“You’re lucky.”

“You have no idea,” I said.

During my high school years, from 1994 to 1997, I worked in the Alzheimer’s unit of a nursing home. It was one of the few places in my suburb of Buffalo, New York, that would hire a 16-year-old, and it took me on mainly because no one else wanted to work there. I had to serve pureed turkey, fish sticks, and peas to people who mumbled or screamed as they swatted their bowls to the ground out of confusion or rage. So much time in close proximity to the dying made me look at my youth as its own form of currency. It was a big world, so I decided I’d better get started seeing it and figuring out who to be within it. Though I didn’t have any means or money, I was confident I could work any awful job as long as it let me explore an interesting place.

So in the spring of 1995, I sent out 30 letters about summer-break jobs in different states. During the summers after my junior and senior years in high school, I took a job at a YMCA camp in Maine. On winter break during my freshman year of college, a New Hampshire ski resort hired me to work in its rental shop. That summer I served hot dogs in Rocky Mountain National Park’s concession stand, my reward being excellent hikes on my days off. Twenty-nine rejections meant nothing if one job came of the effort. The lesson was clear: I could create my own adventure.

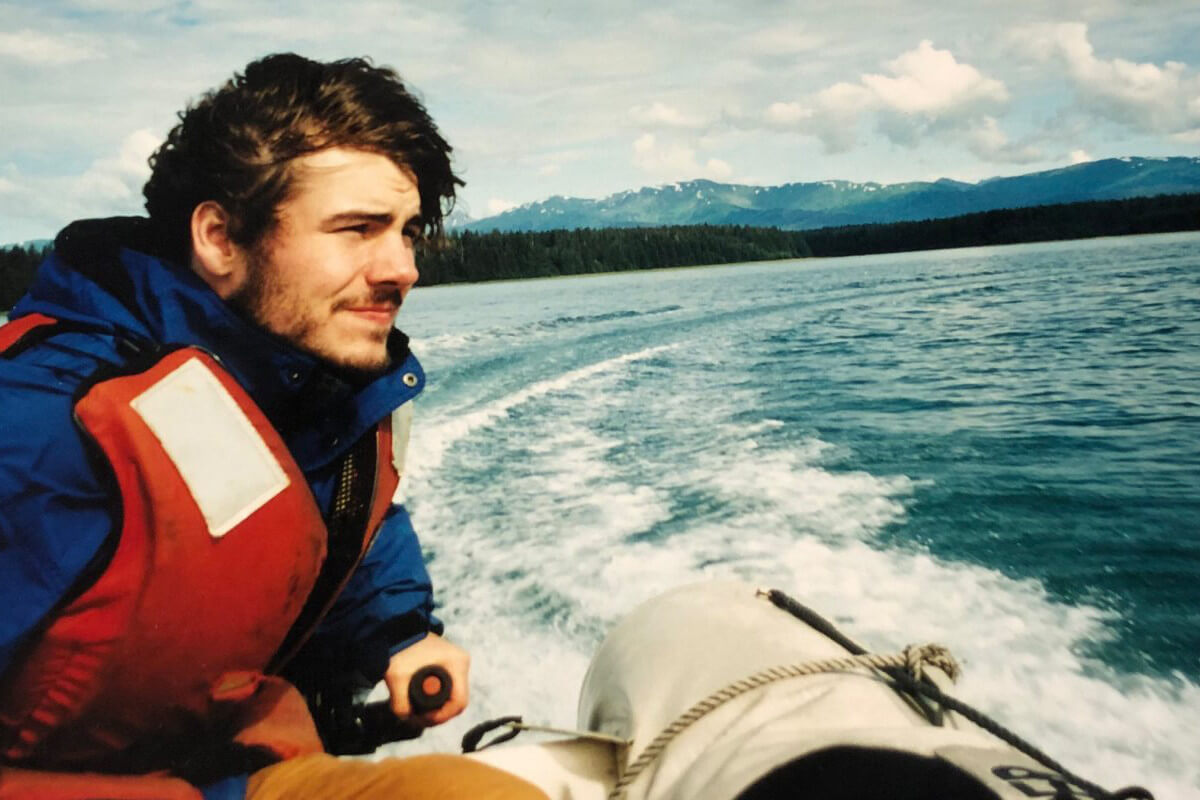

In 1999, during my sophomore year, I sent another 30 letters to tour companies in Alaska, asking for summer employment. To my surprise, I heard back from Glacier Bay Tours and Cruises, which ran a 50-passenger ship called Executive Explorer in the state’s Inside Passage, stopping in Glacier Bay National Park, Tracy Arm Fjord, and a host of small ports.

I flew to Juneau in late May, unsure of what was in store. The pier where I was to meet the ship was crowded with boot-wearing fishermen resupplying a purse seiner. The air was cool and fresh, with a hint of diesel fumes and the muck of low tide. I watched from shore as a three-story catamaran, which looked like a wedding cake on pontoons, roared up to the channel-marker buoys and rode its own wake up to the pier. Its hull and beam were white, with blue lettering on the bow. The upper deck held top-end radar, sonar, and pressure-deployed life-raft canisters. This was all factual information I’d found in its marketing materials. The fact that this ship was coming for me, though, inspired awe.

When the ship was tied off, the captain yelled down from an open bridge window.

“Are you my new deckhand?”

“No. New server.”

“Well. The deckhand didn’t show, so you’re now my new deckhand.”

I had $89 to my name, so I didn’t yell back that I’d never been on a ship before. “Sounds good,” I said.

I boarded, was given a tour, and was taken to a small room under the waterline, where my bunk was one of five adhered to the wall. Once we got underway, the ship rocked with the waves and vibrated steadily from the twin Detroit Diesel engines. Thanks to that combination, my first night as a seafarer was spent heaving into a toilet. At 5:30 A.M., my alarm went off, and I headed out to start my shift. I would work eight hours on, eight hours off, for the next three months.

Twenty-nine rejections meant nothing if one job came of the effort. The lesson was clear: I could create my own adventure.

A nasty, chain-smoking U.S. Navy vet, who worked as an assistant engineer, spent a week showing me my duties. I was to tend to the outer decks, secure the ship and gangway for passengers in each port, and adjust the lines with the tides, which featured extreme swings of up to 24 feet over a single ebb and flow.

“Stay out of the bite of the line, you idiot,” he screamed as I tied off the ship in Haines. “If that line snaps, it will spring loose hard enough to cut you in half.”

He had dark black hair, a pitted face, and an emaciated overall look. He screamed all the time. He screamed while teaching me to do engine-room checks, chip and paint the decks, and secure the gangway.

On a more positive note were all the new things I saw. We sailed into desolate coves and isolated ports. Humpback whales breached next to us. I walked along rivers and found flopping salmon with teeth marks on their sides, put there by grizzly bears who’d been scared off only moments before. Standing on the bow, with my eyes shut and sea mist in my face, felt as much like prayer as anything I’d ever seen or done.

On my night rounds, I often saw the northern lights or heard the sounds of whales surfacing in the dark. While the world slept, I had this. My ego began to make me feel special for having these moments of solitude and grace.

As the summer wore on, my hands became ribboned with cuts from barnacle shards caked into the rope fibers, and I got accustomed to the insults of the assistant engineer, who often tipped over into psychotic rage when I did something wrong. He spent all his free time reading biker magazines and smoking in the dark next to the engines, a patron saint of hatred.

Meanwhile, day by day, I really began to appreciate the passengers. Whether they were recent retirees on a dream trip or industrial business owners leveled by the beauty of the wilds, it was humbling to share in their awakening wonder.

I also got a better sense of the oddity of life on a boat. One time the captain called me to the bridge and told me to man the controls while he went to his cabin. I was 20 years old, steering a cruise ship through the night. It was so exhilarating that, when the captain came back, I didn’t notice at first that he was carrying a full-size test dummy with a long black wig on it. He began dancing around and humming to the doll.

“Um. Sir? What are you doing?”

The captain opened the wing station, sang, “Time for us to part, my love,” and hurled the doll overboard. He blew a kiss to the back of the ship, then called into his radio, “Man overboard.”

He shot a red flare into the sky, and I slowly turned the ship to start our impromptu man-overboard drill. The doll looked so much like a real person that I felt a wash of fear about one day being alone on the waves, drifting off into the cold unknown.

On another night shift, the assistant engineer had me empty the trash locker and dump any biodegradable garbage overboard.

“This feels pretty lousy to do,” I told him while we were cutting open bags over the waters southwest of Cross Sound, in southeast Alaska.

“It will decompose. When you’re 25 miles out to sea, you can dump anything.”

“Anything?”

“Wild West out there. No rules.”

I knew that wasn’t true, but I didn’t argue with him. Toward the end of summer, we docked in Ketchikan next to a ship called The Yorktown Clipper, which was owned and operated by Clipper Cruise Line, a small company based in St. Louis. I walked over and said hello to the deckhand on gangway watch.

“Do you have any more cruises lined up?” I asked her.

“Going south next. The Sea of Cortez. We’re going to get some sun.”

“You’ll keep going?”

“Sure. You should come with us.” She handed me a brochure. The company’s different itineraries were marked with a red line that showed all the tour routes it did. The four ships owned by Clipper, represented by that red line, traced every shoreline on the planet, and at that moment I wanted nothing more than to follow it. I finished my contract for the summer and immediately began plotting my next job on a ship, fantasizing about how far I could go.

During my senior year of college, in 2001, I sent out yet another 30 letters to cruise lines, but then 9/11 tanked the tourism industry. Some of the small ships were laid up in dry dock. Others tried to weather the lack of sales by cruising with four passengers aboard.

The majority weren’t hiring. Very few, if any, hired Americans in the first place. The ships hoist a flag of convenience, which means they’ve been registered in a sovereign nation that’s different from the owners’ home countries. The goal is to avoid regulations, allowing them to run a ship using developing-world labor, cut costs wherever possible, and shirk taxes.

Since getting hired seemed hopeless, I gave up and took a job as a tour guide in Glacier National Park, went to graduate school, and then spent two years as a ball-bearing salesman in Chicago, testing the waters of adulthood. But who can bank their inner fires? I kept writing letters.

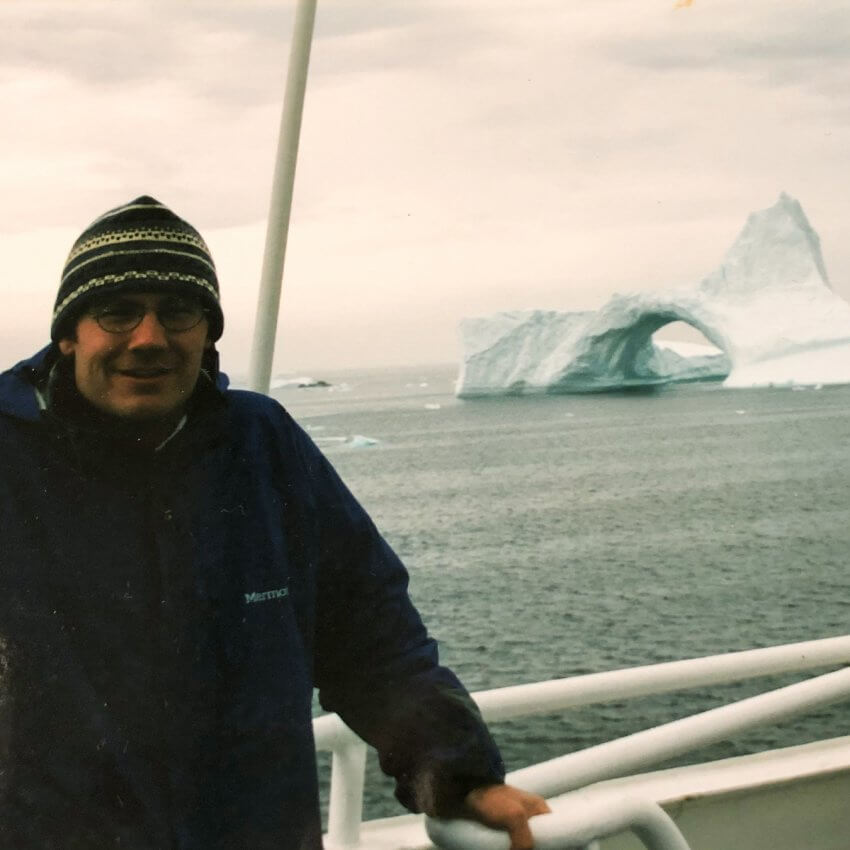

In 2003, the year tourism finally picked up again, someone from Clipper wrote me back. I was hired to work on a 120-passenger international-expedition ship called Clipper Adventurer, flagged out of the Bahamas. I was flown to Glasgow, Scotland, where a ship’s agent drove me nearly two hours up the coast to a small port. After cresting a green, treeless hill, I saw a blue-hulled vessel docked at a small pier. I was jet-lagged but thrilled at the sight. Once on board, I discovered that I was to exist amid an unofficial caste system. The German captain was at the top, followed by a rotating cast of Australian, British, and Irish maritime officers; then Americans who worked as hotel executive, purser, chef, and cruise director; and me, the gopher in the middle, above nearly 80 crew members from the Philippines. My job was to help oversee a professional staff, mostly lifelong shipboard waiters and hotel stewards. There wasn’t anything I could teach them, but they treated me with respect. The entire Filipino crew called me, in earnest, Sir Devin.

On the job, I was quickly outed as having no food-industry training, pronouncing the word crudités a bit too close to “CRUDE-eye-tits.”

“What culinary school did you go to?” the hotel executive asked when he heard this. When I told him I hadn’t attended culinary school, he started an ongoing campaign to have the Clipper’s home office replace me.

But I was a good little servant. I wanted to see everything, and this job could deliver that. So I walked around catering to the wealthy travelers and cowing to the officers above me.

One morning as I was crawling along the ship’s hallway, polishing baseboards, I noticed a passenger, a retired physician named Dr. Gray, standing over me. The day before, he’d found me reading classic novels on the stern and sat down to talk books. For some reason, I told him I wanted to be a writer, a detail I always kept to myself.

“What are you doing to practically pursue your goal?” he asked.

Good question. I’ve since used it to guide my professional life, but I didn’t have an answer for him at the time. I should have held up my books, each one full of notes I’d written as I tried to figure out how they worked. I should have waved my hand at the ship’s wake, a gesture symbolizing the quest for adventure, which is what I desperately longed to write about.

He asked me another question as I scrubbed the baseboards. “Are you doing this so you can say you worked your way up from the bottom?”

“I hope so,” I told him.

“Me, too,” he said.

What was I doing? Somehow I’d hung on to an idealistic notion of youth too long. My college friends were already becoming successful, while I no longer had my own residence or a car. I was 25, and I had to crawl along three more decks on my hands and knees. At this rate, my life would be defined by bosuns and hotel executives doling out menial labor.

For the most part, I grinned through it all, since every day aboard offered a unique story. That first summer, on a Zodiac trip off Canada’s Labrador coast, a polar bear caught our scent and swam a mile to check out our chompable little rubber boat, its head staying above the waves as it neared. While the Zodiac driver took pictures, I pleaded with him to pull away. “It’s getting closer,” I said. “Time to go!” The fear in my voice finally made him reach for the throttle.

When I returned to the ship, I searched for someone to talk to about the bear. I walked into the galley, where our chef had his hands in a vise grip on the head of a five-foot-tall waiter.

“You want to hit me, don’t you?” the chef yelled. “You want to hit me?”

I backed out, but instantly I knew that was a mistake. A moment later, the waiter, angry and hurt, walked out and saw me. He knew I’d seen what was happening and done nothing.

I returned to the galley and found the chef, this time holding his own head. He looked at me and shrugged. “My life is a bag of assholes,” he said.

I didn’t know how he could think that. But I didn’t yet understand the endless hours he spent in this small space, or the frustration he felt interacting with a crew who all spoke Tagalog, when he didn’t, or the hazard that was dealing with the enormous baker’s oven coming loose from its lashings in big seas, rolling around the deck fast enough to pulp him against the bulkhead.

As with my first ship, I slowly began to get a sense of how everything worked, and I soon saw that, along with the various chores I did, my main function was to present a friendly young American face to the mostly American clientele.

I supervised the housekeepers, which is why I was aware that a new Costa Rican marine biologist in cabin 17 had brought up every bit of marine life he could find and stored it in coffee cans. A briny scent filled the corridor: eel slick, fish scales, drying urchins. He dove to the bottom and hauled it all up for guests to see.

When the naturalist pulled me aside, saying, “My cabin reeks of sea turtles and guano,” I smiled tightly and said, “I’ll get you more towels.”

On that first six-month stint alone, I traveled 23,617 nautical miles between the Arctic and Antarctic. I’d work, have a month off, then fly to another ship for my next job. I was getting an education in the complications of life on board and about the world itself.

In the tropics, I used the ship’s satellite phone to call ahead, so that locals would dress up in “war paint” and meet our ship in outrigger canoes. I dealt with outbreaks of the Norwalk virus, fought fires in the engine room, and ran from one food-serving station to the next, frantically cleaning just minutes before health inspectors caught up with me on their tour of the ship. When a housekeeper told me a woman hadn’t taken the “Do Not Disturb” sign off her door for two days, I knocked, opened the door slowly, and apologized for bothering her. Then, when my eyes adjusted, I walked closer.

“Ma’am? Excuse me. Ma’am?”

Closer. Closer. I pressed my fingers into her neck to feel for a pulse, which wasn’t there.

I had to greet the rest of the passengers—who were returning from a tour of Wellington, New Zealand, and boarding the foreword gangway—and distract them from the sight of the port authorities, who just now were taking a body bag off the stern.

“Did you enjoy your tour? Carrot-ginger soup for lunch today!” And please don’t look at the corpse over there.

He shot a red flare into the sky, and I slowly turned the ship to start our impromptu man-overboard drill. The doll looked so much like a real person that I felt a wash of fear about one day being alone on the waves, drifting off into the cold unknown.

During a trip with a nudist company called Bare Necessities that had chartered our ship for the Great Barrier Reef itinerary, two pilot whales began running below our bow. The nudists were led up to the forecastle, where they lined the railing shoulder to shoulder, cheek to cheek, leaning over the front deck to watch the whales gliding along. From the bridge, the crew watched the miraculous sight of 120 bare asses in a packed row.

The captain snapped dozens of pictures. “What a sight,” he said. “What a sight.”

When an American company called Victor Emanuel Nature Tours chartered the ship for bird-watching excursions on the Orinoco River and the coasts of Guyana and Suriname, I was excited because I knew that one of my favorite writers, Peter Matthiessen, often guided trips for the group. Matthiessen didn’t join that trip, but the birders who did were very gung ho, which meant I had to rise as early as 3 A.M., along with the Filipino crew, to start making their breakfasts.

During one trip, I went out with them on the Zodiacs. Some passengers kept asking, “Did you hear that?” and everyone else would say, “Shhhh,” a sort of semi-violent group admonishment.

“There!”

“Shhhh.”

“What was that?”

“Shush!” one woman finally yelled.

“A green aracari,” the tour’s professional naturalist said. He pointed, and there, darting between the trees, was a toucan-shaped bird, a streak of color gracefully drifting through the canopy, which painted its wings in light and shadow.

“Where?”

“Shhh!” I shouted.

For me, the idea of reaching Antarctica felt like arriving at the end of the world. When we got there, near the conclusion of my first stint, I scored an advance look, because I was put in a Zodiac with several others and sent to the continent to get things ready for the passengers. On the ice, I poured champagne and stood among a colony of rockhopper penguins, holding up a tray of glasses. Soon little boats began to ply the water, and I amped up my smile. As passengers came my way, I offered a toast for making it here.

Later that day, back on the ship, we were getting ready for lunch when a pod of orcas was spotted off our stern. The captain worked the ship closer to them; they were still on the surface when he called the hotel executive in the dining room.

“We have orcas. I’m going to announce. Will you hold lunch?”

“Lunch is hot now.”

“Orcas. I have to call it.”

“Please don’t.”

The captain’s voice came over the PA. “Good afternoon, everyone. We have found a pod of orca. Come out. Come out to the decks. A pod of orca.”

From the galley, I heard a plate smash against a wall. The chef was having a fit.

Through a window, I could see a sharp triangular dorsal fin rising up and spinning back into the water. The ship’s engines idled, and the whales began to swim all around us.

I pointed, so that the hotel executive wouldn’t miss the sight of a young orca gliding right under our ship.

“Stupid big piece of sushi,” he said. “I hate this itinerary.” The chef smashed another chafing dish against the galley wall; there was an echo of stainless steel on stainless steel.

“I love the whales,” I said. “No one in my life would believe what I’m seeing right now.”

“Well, that’s how it is,” the hotel executive said. “You live two different lives doing this. You have your home life, but how can you talk about this with people who work on a farm, or at desk jobs? Maybe they think it’s exotic. Maybe that’s why you buy into it yourself. Life on ship becomes your real life after a while. You become a nomad. Your two lives never meet.”

As soon as he said this, I understood what he meant. I had sensed this type of splitting in myself.

Later, in the middle of the night, an enormous wave hit the ship. I was lifted out of my bunk and sent flying into the wall on the far side of the cabin. My belongings crashed on top of me before the ship righted itself and tossed me back onto my mattress, where I got a firmer grip and pressed my chest down, in hopes of getting a few hours of sleep before my shift started. I can’t recall the exact moment when I stopped feeling panic and fear at times like this. Acceptance of what was beyond my control became essential.

During our return trip from Antarctica, the Drake Passage—the expanse of ocean between Antarctica’s South Shetland Islands and Cape Horn—thrashed the ship around. The hotel executive, feeling sick, went to his cabin and left an Excel spreadsheet open on a computer we shared. It showed what the international crew members were paid, and their low compensation—far less than minimum wage in the U.S.—stunned me. I was able to save much of what I made. These men, who worked with kindness, effort, and attention to detail for 12 hours a day, six days a week, and up to nine months at a time, were being exploited, and they had to send money to families back home. The reality of the flag of convenience became clear.

In 2004, as we rode out another storm along the west coast of Panama, the hotel executive found the Filipino crew “slacking off” instead of deep-cleaning the empty cabins. He sent me to yell at them.

“They’re not your friends,” he said. “This is your job.”

When I found them sitting on the edge of their beds inside their cramped space, I shouted, “Why aren’t you working?”

“We’re all a bit seasick,” one of the waiters said, and I was instantly ashamed. Yet I kept screaming at them. Not because I wanted to, but because I was a coward and didn’t want to slide down, or off, the ship’s caste system.

My college friends were already becoming successful, while I no longer had my own residence or a car. I was 25, and I had to crawl along three more decks on my hands and knees.

After all this, I stepped out onto the lido deck. We were approaching the mouth of the Panama Canal, where hundreds of vessels waited in line for their transit. Giant cargo ships with multicolored stacked containers. Car carriers. Iron-ore and oil tankers.

There were so many ships. All had foreign flags, and only now could I really imagine what living on them must be like. I’m an American who grew up surrounded by comforts that were delivered to me by ships like these—ships that I’d never thought about.

For me as a young man, and maybe for all youth who thirst for adventure, the goal was to test myself, to discover the type of person I would become. This sort of work, which often made me feel small and came with so many bizarre challenges, also helped me forge a deep sense of right and wrong on a global scale, gain self-confidence, learn to always expect surprises, and constantly look for beauty in everything. I felt awful on that lido deck—I’d betrayed the crew and myself—but around me those ships, fraught for so many reasons, were also beautiful and represented a world constantly pushing toward progress. Once I found the world to be beautiful, wherever in the world I was, it became easy to love it for its complexity.

I eventually served on all four of the company’s ships and worked my way up to the job of cruise director and expedition leader. On one of those trips, in 2005 aboard the Yorktown Clipper in maritime Canada, Dr. Gray appeared again, walking up the gangway. I welcomed him aboard in my officer’s dress uniform.

“This does not surprise me,” he said, smiling. Then he walked down the hallway. I’d set an unlikely goal to work my way around the world and had done so. What I took as Dr. Gray’s small nod of acknowledgment made me feel equal to any task I set for myself.

I still enjoyed ships, and I loved helping deliver life-changing experiences to passengers. But I was growing deeply lonely, and saw that if I kept going, I would end up a bachelor at sea. Many of my coworkers had become a bit warped from loneliness, and the roiling mess of want and need behind the facade of courteous and happy workers unsettled me. Part of me was wild and adventurous; the other a servant. My dream job had become much more job than dream. But I was going to ride it to the end.

That end could have come with my bout of depression along the Kamchatka Peninsula, at a time when I had not seen the sun for two months. Or when Clipper Cruise Line sold the ship I was working on, and therefore my services, to Cruise West. Or maybe that time in Marrakesh when passengers complained about not having enough extra towels after a tour of a market, where we’d passed destitute people begging for change. It could have come in Indonesia, when we ferried passengers to shore for a traditional welcome from a native tribe. They were told that we had no way to help them get local art home, so they shouldn’t buy anything, yet they proceeded to buy spears, shields, and 40-foot-tall totem poles. An 84-year-old woman, as she was stepping back onto the ship, handed me something she’d bought from a dancer.

“What’s this?” I asked.

“A penis gourd.”

I was tired of watching people take from the sky, the sea, and the backs of locals. But I kept going until the fall of 2007, when after six ships, three companies, 50 countries, and all seven continents, I finally decided I’d had enough.

When I think now of why I left, the moment that comes to mind is the time I was sent ashore to a small island off the coast of Papua New Guinea with a serrated bread knife to cut palm fronds to decorate the back of the ship for a passenger barbecue. On a rainy beach, I saw more than a hundred islanders who were out to meet our ship in war canoes, each man holding a machete or spear and using palm fronds as umbrellas. I didn’t even know what language they spoke. Stepping onto that beachhead brought the merits and irony of my life into such a ridiculous and stark view that I’ve been trying to make sense of it ever since.

Soon after I gave up the voyaging life, the 2008 recession hit. Cruise West later folded, and all over the place ships were laid up and crews laid off, and it would take a while for them to come back, a while until there was space for young, adventure-hungry crew to climb aboard again. These days, with COVID-19, most of the ships are again not sailing, and I imagine that wanderlust is compounding in a generation of young people who I hope will someday have jobs at sea, in national parks, at ski resorts, and in all the other lovely and wild places of the world. I want that for those who may be, like I was, needing to see so much in order to find their way.

What I wanted most was to gather stories and experience it all. I wanted that so badly. To unhinge my jaw and swallow the world. Perhaps I knew I needed to spend all my youthful energy, so there would be none left to sour into regret. Looking back, I’m so happy to have had this treasured adventure on ships that went everywhere. My cabin’s porthole gave me a view of several oceans as the ships flowed down tropical rivers and rubbed against giant icebergs; on any given night we might pull up alongside the Sydney Opera House, Chelsea Pier, or a rank dumpster in Port Moresby. For so long, everything drifted: The ship. The clouds. The people. The creatures underneath. Everything. Including me.